RAPTOR(Rapid Algorithmic Prototyping Tool for Ordered Reasoning) is a free graphical authoring tool created by Martin C. Carlisle, Terry Wilson, Jeff Humphries and Jason Moore, designed specifically to help students visualize their algorithms and avoid syntactic baggage.

Students can create flow-chart for a particular program and raptor tool will generate code for it in various programming languages, such as C, C++, Java and so on.

- Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Tool

- Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Printable

- Raptor Slot Machine Flow Charts

- Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Diagram

RAPTOR is a flowchart-based programming environment, designed specifically to help students visualize algorithms and avoid syntactic baggage. RAPTOR programs are created visually and executed visually by tracing the execution through the flowchart. Required syntax is kept to a minimum. Students prefer using flowcharts to express algorithms,. Download this Free Vector about Casino isometric flowchart, and discover more than 9 Million Professional Graphic Resources on Freepik.

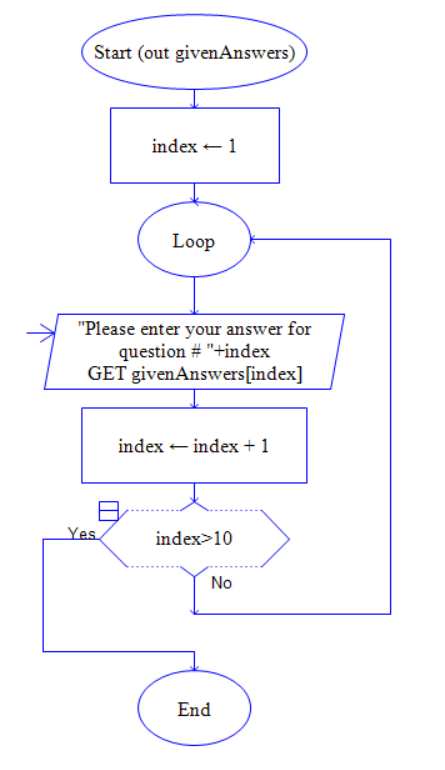

Symbols in RAPTOR

Raptor has 6 types of symbols, each of which represents a unique kind of instruction. They are – Assignment, Call, Input, Output, Selection and Loop symbols. The following image shows these symbols-

RAPTOR Program Structure

A RAPTOR program consists of connected symbols that represent actions to be executed.

- The arrows that connect the symbols determine the order in which the actions are performed.

- The execution of a RAPTOR program begins at the Start symbol and goes along the arrows to execute the program.

- The program stops executing when the End symbol is reached.

With the help of Generate option, the generated C++ code for the above flow chart is:

#include <iostream>intmain() string raptor_prompt_variable_zzyz; cout << raptor_prompt_variable_zzyz << endl; if(m>=90) cout << 'The grade is A'<< endl; } { { elseif(m>=60) cout << 'The grade is C'<< endl; } { } } |

In this way, any algorithm can be visualised by the students, and it can be converted into a code using the raptor tool.

This article is contributed by Mrigendra Singh. If you like GeeksforGeeks and would like to contribute, you can also write an article using contribute.geeksforgeeks.org or mail your article to contribute@geeksforgeeks.org. See your article appearing on the GeeksforGeeks main page and help other Geeks.

Please write comments if you find anything incorrect, or you want to share more information about the topic discussed above.

Recommended Posts:

Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Tool

By Donald Morris, Ph.D., MS, CPAExecutive Summary

Most taxpayers believe gambling proceeds are immune from tax, unless they receive a Form W-2G.

Each pull of a lever or push of a button on a slot machine, hand of blackjack or spin of a roulette wheel is an individual wager that may result in gambling winnings.

To prove gambling losses and taxable income, taxpayers are subject to rules of proof, recordkeeping, estimating and credibility.

Taxpayer-gamblers are not generally aware of the ease with which the IRS successfully counters attempts to offset gambling winnings with gambling losses. Often, gamblers are not concerned about the exact amount of gambling winnings they report, because they believe they have sufficient gambling losses to offset their winnings. The central issue raised by the Service on audit is not always the right to a deduction for gambling losses—allowed by Sec. 165(d)—but taxpayers’ inability to prove the amount of their gambling losses and, in particular, their basis in the losses claimed.

The Problem of Gambling Losses

A common scenario involves a taxpayer, as in Norgaard,1 who reports gambling winnings because a Form W-2G, Certain Gambling Winnings, was issued. The fatal step is that the taxpayer dutifully reports the W-2G winnings, but fails to report any other winnings, however small. The IRS, on examination, questions the gambler about the possibility of any other winnings during the period. When the taxpayer admits to other winnings, the Service asserts that whatever the amount of the taxpayer’s losses, they were already used to offset the unreported winnings and, thus, are not available to offset the W-2G winnings. The Tax Court has accepted this position when the taxpayer failed to report gambling income in excess of W-2G winnings. The taxpayer must establish that claimed gambling losses exceed unreported gambling income, to be entitled to a deduction.2

When the IRS determines that a taxpayer’s income is incorrectly computed, he or she bears the burden of proving that the Service’s position is erroneous.3 In Mack,4 the Service successfully denied gambling losses, arguing that the taxpayer’s losses were already offset by winnings other than those reported on his return. In Lutz,5 the IRS conceded unproven gambling losses of $43,818.75 to the taxpayers, then asserted they were not entitled to a deduction, because those losses were less than the unreported gross gambling winnings omitted from the notice of deficiency. The court responded that, to establish their entitlement to deduct gambling losses from gross gambling income, the taxpayers had to show that their gambling losses exceeded the $50,995 of unreported gross gambling income not reflected in the notice of deficiency. This approach may save the Service from having to reconstruct a taxpayer’s unreported winnings, which can be daunting.6

A taxpayer’s logical response to the IRS should be to produce his or her books and records regarding the year’s gambling activities, as required by Rev. Proc. 77-29.7 This procedure requires taxpayer-gamblers to maintain an accurate diary or similar record, supplemented by verifiable documentation of wagering winnings and losses. The diary must contain the following information:

1. Date and type of specific wager or wagering activity;

2. Name and address or location of gambling establishment;

3. Name(s) of other person(s) (if any) present with the taxpayer at the gambling establishment; and

4. Amounts won or lost.

For slot machines, the Service further requires that a taxpayer record all winnings by date, time and slot machine number (see Exhibit 1). But because few taxpayers (especially recreational gamblers) maintain convincing records of their gambling activities, they can be left paying tax on their gross W-2G winnings, without any offset for gambling losses. Unreported W-2G winnings can also result in the imposition of penalties and interest.

In Kalisch,8 the taxpayer reported $41,979 in gambling income and claimed offsetting gambling losses in the same amount on his 1981 return. In its notice of deficiency, the IRS accepted the taxpayer’s income figure, but disallowed the deduction for gambling losses, because the taxpayer failed to substantiate them and because he had additional unreported winnings that exceeded his losses for the year. The court rejected the additional-income argument and allowed the loss deduction. Fortunately for taxpayers, the courts do not always agree with the Service’s reasoning.

A Growing Problem

What is the potential magnitude of this problem? Should practitioners and their clients be concerned? Part of the answer lies in the growing number of people participating in gambling. In 2000, the U.S. General Accounting Office reported that legalized gambling had spread to every state, except Utah and Hawaii.9 Legalized gambling in the U.S. has seen a steady increase since the advent of Indian tribal casinos and the subsequent legalization of casino gambling by states other than Nevada. Gaming revenue for 2002 totaled $68 billion (up from $30 billion in 1992, or 127%), while in 2003, it totaled $73 billion, rising 7.4% from the previous year.10 Of this total, $40 billion stems from casino revenue.11 In addition, for 2004 (the most recent data available), 1.7 million taxpayers reported gambling winnings to the IRS totaling $23.3 billion. This is up from the 1.5 million taxpayers in 2003 who reported winnings of $19 billion.12 An estimated 86% of Americans have participated in gambling in some form, and 63% reported gambling at least once in the past year.13 The number of individuals visiting casinos in 2003 was 53 million—more than one quarter of the U.S. adult population.14 Tax advisers should assume the same percentages apply to their clients, as gambling cuts across demographic and regional boundaries. As one tax observer recently noted, “Gambling is increasingly looked upon as a legitimate entertainment option akin to sporting events, the theater, and amusement parks.”15 What are the practical consequences of the spread of gambling?

As with other areas requiring recordkeeping (such as automobile mileage and entertainment), clients must be informed of the legal requirements for reporting gambling winnings, even if they erroneously believe they have no reportable winnings or they have sufficient gambling losses to offset them. It is crucial to determine gross gambling winnings and to separately establish the amount and basis for deducting gambling losses. As noted, the IRS wields a powerful argument in its arsenal; taxpayers and their advisers need to be educated.

Educating Clients

Education covers two fronts. First, which types or amounts of gambling winnings must be reported? The requirement to report gambling winnings (legal or illegal) at gross, even if the year’s net result is a loss, is not frequently recognized by taxpayers, including recreational gamblers. Gross gambling income is reported on page one of Form 1040, while gambling losses are a miscellaneous itemized deduction (not subject to the 2%-of-adjusted-gross-income (AGI) limit).

Taxpayers often believe their winnings are immune from reporting unless they receive a Form W-2G. In Hamilton,16 taxpayers failed to include $134,041 in lottery winnings in income on the grounds that they were neither professional nor part-time gamblers. The court disagreed, asserting that “an accession to wealth on account of gambling winnings is includable in an individual taxpayer’s gross income whether he or she is a professional gambler, a part-time gambler, or simply a onetime gambler.”

Taxpayers must also segregate winnings from losses to allow proper reporting. In Clemons,17 the taxpayer argued that his $44,833 in gambling winnings need not be included in gross income, because he had sufficient gambling losses to offset them. According to the court, the taxpayer “steadfastly rejects or ignores certain basic principles of the Federal income tax laws.” The taxpayer insisted on netting his winnings and losses and reporting only net winnings on his return.18

Once the need to report gambling, like any other form of income, is established and the corresponding requirement to segregate (as opposed to netting) winnings and losses is acknowledged, the next step is establishing a basis for gambling losses.

Tax Adviser’s Responsibility

Tax advisers need to recognize the pitfalls involved in determining the amount of gambling losses available to offset winnings. As most taxpayers do not keep sophisticated books and records of their gambling activity, the tax preparer is in a potentially perilous position when advising a client on documentation requirements for establishing gambling losses. If the taxpayer is reporting Form W-2G winnings (and no other gambling income), a preparer should not take a taxpayer’s word for the fact that he or she suffered sufficient offsetting losses without at least discussing the issue of documentation and the Service’s expectations in Rev. Proc. 77-29. The IRS and the courts, for example, view the documentation required for gambling no differently from that for employee business expenses, charitable donations, casualty losses and medical expenses. In Schooler,19 the court stated that there is no reason to treat taxpayers who claim deductions for wagering losses more favorably than other taxpayers by allowing a deduction for wagering losses when the evidence is inadequate.

Calculating Gambling Income

Sec. 165(d) allows a deduction for losses from wagering transactions only to the extent of gains therefrom.20 Gambling winnings are defined in Sec. 3402(q)(4)(A) as proceeds from a wager that is determined by reducing the amount received by the amount of the wager. Literally construed, this means that each pull of the lever or push of the button on a slot machine, hand of blackjack or spin of a roulette wheel is an individual wager that may result in gambling winnings.

The Service’s position is: “a gambling gain is the difference between wagering proceeds received and the amount wagered on a gambling transaction. I.R.C. section 1001(a) defines gain as [the] difference between amount realized and [the] adjusted basis.”21 However, the IRS also admits a problem with the position that the cost of a winning wager should be excluded from gross income. In determining what constitutes a winning wager, it concedes, '[t]here is a definitional problem of one gambling transaction.” (Emphasis added.) The Service’s guidance continues, “[a]lthough the purchase of a lottery ticket or a bet on a horse race seems to be an individual transaction, one hand of a poker game or one pull of the lever of a slot machine may not be one gambling transaction. This seems to be a factual issue which varies in accordance with the nature of the wager.” In Letter Ruling 8123015,22 the Service stated that a wagering transaction for purposes of withholding taxes is one in which all wagers are identical because bets are placed on the same animal (or team) to win the contest. If the wagers are not identical, there is more than one wagering transaction.

Further, according to the Service, each bet on a different possible winning combination is a separate wagering transaction for purposes of determining taxable income. It is apparent from this that, because each bet on a slot machine is a bet on a different set of contingencies programmed for the machine, each push of the button is a different gambling transaction. While it is clear that there may be a “definitional problem” in determining what constitutes one gambling transaction, it is not obvious that a practical distinction can be established between an individual bet on a horserace and an individual hand of poker, or between an individual lottery ticket purchase and a single push of the button on a slot machine. The key to resolving this issue may reside in application of the constructive-receipt doctrine.

Constructive Receipt

Because individuals usually report their income on a cash basis, the constructive-receipt doctrine applies to their gambling transactions, as well as to other accessions to wealth. Constructive receipt means that income occurs when the taxpayer has the opportunity, whether exercised or not, to draw on the cash freely.23 The crux of constructive receipt is essentially unfettered taxpayer control over the time funds are actually received; control is not subject to any substantial limit or restriction. In this respect, gambling is analogous to earning interest on a savings account, but not actually retrieving it.24 The interest (or the gambling transaction winning) is taxable when available for withdrawal; whether one chooses to remove the cash at that point or leave it on account (in the slot machine or on the blackjack table) is irrelevant to its taxability.

Based on this reasoning, each winning or losing wager should constitute a gambling transaction, because a gambler could stop betting after any given wager. Thus, winnings (and losses) should be tracked for each individual bet, not, as many (most) gamblers (anecdotally) assume, on the basis of the day’s (or year’s) final tally. Reporting the outcome of each wager results in reporting gambling winnings at gross—as the law requires—and in an objectively determinable manner (although cumbersome, because of the recordkeeping). Without this interpretation of a gambling transaction, reporting losses separately from winnings becomes subjective and places the taxation of gambling gains effectively at the taxpayer’s discretion.

Slot Machine (In-Out) Reports

Exhibit 2 is a sample report issued by casinos to slot machine players who register for the casino’s “Players’ Club” and use the card to record their slot machine play. The Players’ Club cards are magnetic-strip cards inserted by the gambler into the casino’s slot machines, which electronically track the player’s wins and losses.25 Taxpayer-gamblers who frequent casinos will often have this report available in their tax records.26

The win/loss amount is net; its accuracy hinges on several factors. The first is the consistency of the taxpayer’s use of the card when playing slot machines. (If he or she played at more than one casino, was a card used at each? Was the card employed at each machine? Did anyone else use the card?) The second is the taxpayer’s record of cash available before playing the slots, as well as after playing them; the “dollars in” figure includes amounts bet plus amounts placed in the machine’s currency accepter, but does not break them out. If the slot player cashes out the same amount he or she originally placed in the machine (i.e., breaks even), the amounts wagered and won are reliable indicators of gross winnings and wagers (given the above limits). If this is not the case, the win/loss amount must be adjusted by the change in cash position from the beginning of play to the end.27

The columns are calculated as described in Exhibit 3, which includes comparing amounts wagered to winnings and cash at the outset with cash at the end.

Taxpayer-gamblers are sometimes shocked by the numbers presented in the report in relation to their memories of actual amounts wagered. This results in part because “dollars in” represents not only the amount originally placed in the slot machine, but also the cumulative wagers—although the amounts wagered were likely never available to the gambler at any one time.28

Example 1: A gambler placed $2,000 of his own funds into slot machines over the course of a year. These wagers, together with credits from winning bets, generated cumulative wagers of $10,375.75, of which $8,729.50 was derived from winnings ($2,000 was cashed out). The result is a $1,646 net loss; see Exhibit 4.

The “dollars out” column includes winnings plus funds cashed out, if any (not including jackpots, which are paid by hand and reported separately). In this example, the amounts originally deposited in the slot machine plus the amounts wagered exceed the amounts won plus dollars cashed out. When the hand-paid jackpot of $1,200 is subtracted, the loss is reduced to $446.25, as indicated in the report in Exhibit 2.

Reporting Losses

The fact that a taxpayer incurred a net loss for a year does not relieve him or her of the obligation to report winnings. In Exhibit 2, the Form W-2G received for the $1,200 jackpot will likely encourage the taxpayer to report such winnings on his return. The Exhibit 2 report states that there was a net loss for the year; this may lead the taxpayer to conclude that a $1,200 deduction in offsetting losses is warranted on Form 1040, Schedule A. This is how the problem of demonstrating a basis for losses arises, because the losses on the report are linked to income that may be unreported.

It is up to the taxpayer to establish the out-of-pocket amount ($2,000 in Example 1). The process of establishing gross winnings requires the taxpayer to prove the amount originally wagered, as well as the funds remaining at the end of a gambling session. The IRS lists bank records as one means of corroborating amounts gambled; thus, taxpayers can accomplish this by making automated teller machine (ATM) withdrawals at the casino and retaining these records. After the amount of the taxpayer’s own funds provided and retained is determined, he or she can establish gross winnings and losses from the in-out report. While it may appear that basing gross winnings on the “dollars out” balance (less amounts cashed out) involves reporting “phantom winnings” (because the winnings are never available all at one time), it is also the starting point for establishing a basis for losses realized and is needed to segregate winnings from losses.

Erbs

In Erbs,29 the taxpayer, with an AGI of $27,865, had visited a casino on 88 days in 1996. The taxpayer reported as his gambling gross income jackpots listed on Forms W-2G totaling $10,538. He also indicated to the court that casino records recorded a “dollars in” total of $368,166.95 and a “dollars out” balance of $341,530.20; see Exhibit 5.

To determine winnings from the report, it is necessary, as was noted, to know how much of the taxpayer’s “dollars in” came from his own funds (pre-winnings). The taxpayer testified that he visited the Ho-Chunk Casino in Baraboo, WI on 88 days during the year. On each occasion, he withdrew from an ATM to finance the day’s gambling. The total supplied by the taxpayer is not indicated; however, assuming that his daily bank ATM limit was $300, this would amount to $26,400 (88 × $300) of his own money. If the taxpayer used no other funds for his slot machine play, his wagers would constitute the balance of the “dollars in” amount, $341,766.95 ($368,166.95 – $26,400). The taxpayer’s loss would then be the difference between the amounts wagered and the “dollars out” amount, which represents slot machine winnings (less amounts cashed out, if any). Reporting the grossed-up winnings in the Erbs example results in an increase to AGI of $315,130.20 (assuming funds cashed out equaled funds at the start of play).30

Establishing Basis for Losses

As was noted, a taxpayer who fails to report his or her gambling winnings in full, then loses some or all of these winnings, has no basis in the losses and, thus, nothing to deduct. According to Alsop,31 “[a] taxpayer may not take a loss in connection with an income item…unless the income item has been previously taken up as income in the appropriate tax return.” It is only by reporting all winnings (even if those winnings—in the form of “house money”—are re-bet and subsequently lost), that a taxpayer can establish a basis in all his or her losses.32 In Erbs, this would mean reporting $315,130.20 in winnings, plus $10,538 of jackpots, and deducting $341,766.95 in losses (limited to winnings)—adjusted for the difference between original funds available at the beginning and those available at the end33, see Exhibit 6.

In Mack, the taxpayer admitted he won other wagers during the tax year, but testified he sustained corresponding offsetting losses that were not included in the amount deducted as a loss. The court registered its skepticism, asking whether the taxpayer had not already included some of these “corresponding” losses in the claimed losses. The court noted that the taxpayer had the burden of showing that the funds used for making wagers were either on hand at the beginning of the year, or were acquired during the year from nonwagering sources. It concluded that he failed to make this showing. Failure to recognize winnings means that if those winnings are re-bet and lost, the taxpayer has no basis in those losses, and, thus, nothing to deduct.

Recordkeeping

Sec. 7491(a) places the burden of proof on the Service with respect to any factual issue relating to tax liability, as long as the taxpayer maintained adequate records, satisfied the substantiation requirements, cooperated with the IRS and introduced credible evidence as the factual issues. Sec. 6001 and its regulations prescribe the recordkeeping requirements applicable to all taxpayers, including gamblers. In Kikalos,34 the court stated that taxpayers must maintain accounting records of gambling activities that enable them to file accurate returns. When a taxpayer fails to maintain or produce adequate books and records, the Service is authorized to calculate the taxpayer’s taxable income by any method that, in its opinion, clearly reflects the taxpayer’s income. The IRS’s determination of taxable income in such cases is presumptively correct; its method need not be exact, but must be reasonable in the context of the available facts and circumstances.

In Rodriguez,35 the taxpayer argued that accurate records of gambling losses and winnings are difficult to maintain. He testified that the “very nature of the business makes this task daunting, if not impossible.” The Service countered that the taxpayer did not prove the amount of his gambling losses or that they exceeded his unreported gambling winnings. Implicitly, according to the court,

this requires the taxpayer to prove both the amount of his losses and the amount of his winnings. Otherwise there can be no way of knowing whether the sum of the losses claimed on the return is greater or less than the taxpayer’s winnings.…If the taxpayer, in addition to the winnings reported on his or her return, received other winnings that were not reported, then the taxpayer must prove that the losses claimed in his or her return exceeded the unreported winnings in order to be entitled to deduct any such losses. (Emphasis added.)

The court concluded that the taxpayer’s contention, that maintaining accurate records of gambling losses and winnings is difficult, is insufficient to counter the Service’s determination. All taxpayers, it held, are required to substantiate their deductions under Sec. 165(d), and the taxpayer is being held to the same standard imposed on all taxpayers.

Taxpayer Credibility

In another case,36 a recreational gambler had won at least 29 horserace wagers during 1996, totaling $32,050. He reported none of the winnings, asserting that they were nontaxable because his offsetting gambling losses during the year exceeded $70,000. However, the taxpayer failed to document his losing wagers, and relied “primarily on his [own] testimony to prove his allegation.” The court found his testimony not to be credible and declined to rely on it. Although the court acknowledged the taxpayer most likely had some gambling losses during the year, it was unable to determine (either with specificity or by estimation) those losses on the evidence presented.

In Mack, the court accepted as evidence of gambling losses 15 checks payable to the Detroit Race Course. In his testimony, the taxpayer admitted that it was unusual for bettors to cash checks at racetracks, but explained that they had been accepted by a course official who was a long-time friend. While accepting the checks as evidence of some gambling losses, the court did not find the taxpayer’s evidence adequate to substantiate the full amount of his claim.

Less-Credible Taxpayers

In Stein,37 the court ruled on the adequacy of a professional gambler’s books and records. It stated that a summary record of income and expenses prepared at the end of the year (rather than during the normal course of the taxpayer’s business) is inadequate substantiation. Likewise, a condensed record made contemporaneously during the year, but unsupported by records of original entry, is also insufficient. The taxpayer claimed that his records of original entry, recording his gambling activities, were scratch paper notations prepared daily, based on increases and decreases in his bankroll, and a notebook prepared at the end of the year from these notations. The notebooks did not contain original entries, but “disclosed a running balance interspersed with dated entries which purport to show winnings (listed as ‘in’) and losses (recorded as ‘out’).”

Stein followed the practice of recording at the end of each day an amount purported to represent his net gain or loss for the day from gambling transactions. He recorded these amounts (preceded by a “W” or “L”) on any scrap of paper he could find handy such as a match folder, scrap of note paper, cocktail napkin, scratch pad, soap wrapper, postcard, score card, gin rummy slip, etc. He kept these various slips of paper in his pocket until he returned home where he placed them in a drawer and retained them until the end of the year. After the close of each of the years in issue he collected all these scraps of paper containing dated entries preceded by a “W” or “L” and copied the entries in a small notebook. He afterwards destroyed the various pieces of paper.

The court found this method of recordkeeping inadequate to establish gambling losses and their basis. The taxpayer’s notebooks did not contain details of any of his gambling transactions, nor disclose the identity of any of his bettors. Because the original records had been destroyed, the veracity of the notebooks could not be verified. Had he retained the records of original entry, each dated and including pertinent identifying detail (e.g., numbers of bets, amounts bet, source of funds, kinds of wagers, individuals involved and payments received), the court might have been less reluctant to accept his notebooks as adequate.

Credibility of the Records

In Green,38 a pro-taxpayer case, the court characterized the IRS’s position as follows: “The total amount of wins can be accepted as an admission against interest while the amount of total losses is merely a self-serving declaration which must be proven by verifiable data.” According to the court, the taxpayer supplied original records of a gambling partnership that reported wins, losses, expenses, payroll disbursements, distributions to partners and a running balance of the partnership bankroll. Contrary to the Service’s position, the court found that the failure to account for gross receipts and gambling disbursements did not justify totally disregarding daily net-loss figures when it was shown that those amounts were obtained from “orderly records and, when subtracted from the amounts reported as net wins, are sufficient to calculate gross income and net income.”39 Thus, in Green, a journal reflecting daily gambling activity, but failing to show total wins and losses, was superior to a year-end record, as in Stein, showing totals but lacking detail sufficient to generate them.

The Cohan Doctrine

Cohan40 is often cited by the courts in the context of gambling losses. In Zielonka,41 in which a court disallowed the deduction of gambling losses, it stated that, if the trial record provides evidence that a taxpayer actually incurred a deductible expense, but the evidence is inadequate to substantiate the amount of the deduction to which the taxpayer is entitled, the court may estimate the expense and allow that amount as deductible (the allowance of an estimate is known as the Cohan doctrine). In such cases, the court can only estimate the deduction if provided with some basis to make the estimate. In Zielonka, the taxpayer was not allowed to deduct $140,830 of gambling losses to offset gambling winnings of a like amount. The court noted that a taxpayer’s gambling losses are based on the facts and circumstances and must be decided on the evidence presented.

In Drews,42 the court applied the Cohan doctrine and found the taxpayer sustained net gambling losses. The taxpayer had failed to keep records of gains or losses from his gambling transactions, but claimed a deduction for gambling losses to partially offset his $9,000 gambling winnings from a single horserace. Gambling losses were allowed, but in an amount less than claimed by the taxpayer. In justifying its findings, the court stated, “We are convinced, on the whole, that petitioner…was a truthful and candid witness.”

In Doffin,43 the court estimated and allowed IRS-rejected gambling losses. The court looked at the taxpayer’s lifestyle and history, which included the sale of personal assets (rather than their purchase) and debt acquisition to finance gambling activities. According to the court, the taxpayer had few other assets that would “indicate any significant accessions to wealth.” In the years in question, 1986 and 1987, the taxpayer reported Form W-2 wages of $14,717 and $12,540, respectively. Ignoring the economic realities, the Service attributed gambling winnings of $46,240 and $32,771 to the taxpayer, with no offsetting deductions for losses. The court reasoned that if the taxpayer had winnings in those amounts, most of them must have been used to finance additional gambling, most of which resulted in losses. The losses were estimated by the court at $39,000 and $26,000, respectively, for the years at issue. Aiding the court in applying the Cohan doctrine was the taxpayer’s testimony, which it found “honest and credible.”44

Strategy

So many courts have refused to apply the Cohan doctrine to gambling losses that taxpayers and their advisers should not feel comfortable relying on a court to make such estimates.45 A better strategy is to maintain adequate, detailed, contemporaneous records of winnings and losses. Corroborating evidence is essential in establishing basis for gambling losses. The Service and the courts look at lifestyle, large cash purchases, levels and use of debt, credibility of testimony and bank and credit card records. For slot machine players, the conscientious use of a Players’ Club card may be a first line of defense in dealing with the IRS, not merely a means for obtaining comps and discounts from the casinos. In using this documentation, the taxpayer must also track the amount used for gambling (original cash supplied, not current winnings) and the amount cashed out of slot machines and retained.

Many recreational gamblers establish a loss limit before an excursion to the casino; when that money is gone, they stop gambling. If this is the case, the use of in-out reports to establish the basis of losses and gross winnings is made easier. Because these gamblers keep wagering until their pre-established loss limit is met, only the beginning cash balance for each casino visit must be demonstrated. If this amount is subtracted from the “dollars in” total, the balance is the amount wagered. The “dollars out” total, if there are no amounts cashed out (i.e., the cash loss limit was met), is the taxpayer’s gross winnings. The result is a credible third-party record of gross winnings or losses.

Conclusion

Advising and preparing returns for the growing number of individuals engaged in recreational gambling is a difficult proposition, partly due to the gap between the IRS’s expectations as to recordkeeping and taxpayer-gamblers’ beliefs and attitudes. A tax adviser is faced with educating clients as to the requirement to report winnings separately from losses and to report gross winnings (which include house money won and subsequently lost). Clients must also be informed that they have the burden of proving that the funds used for making wagers were either on hand at the start of the year or their acquisition during the year was from nonwagering sources.46 This burden is a difficult hurdle, especially in the context of an activity generally engaged in for pleasure and diversion. Maintaining clear, contemporaneous records of both winnings and losses is the only trustworthy defense a taxpayer (even a recreational gambler) can produce that will prove effective against a Service challenge to gambling loss deductions.

For more information, contact Dr. Morris at Dmorr2@uis.edu.

Notes

1Preben Norgaard, TC Memo 1989-390, aff’d on one issue and rev’d on another, 939 F2d 874 (9th Cir. 1991).

2 See, e.g., Robert M. Kalisch, TC Memo 1986-541, aff’d in unpub. op., 838 F2d 461 (3d Cir. 1987); Carolyn J. Schooler, 68 TC 867 (1977); and Clifford F. Mack, TC Memo 1969-26, aff’d, 429 F2d 182 (6th Cir. 1970).

3 U.S. Tax Court Rule 142(a); Welch v. Helvering, 290 US 111 (1933).

4 Mack, note 2 supra.

5 Ronald J. Lutz Jr., TC Memo 2002-89.

6 In Lutz, id., the court pointed out that had the IRS wanted to introduce at trial the amount of unreported gambling winnings (which were not listed in the notice of deficiency), it had the burden of proving this amount. The Service may have been able to reconstruct the amount based on large asset purchases mentioned in the case.

7 Rev. Proc. 77-29, 1977-2 CB 538.

8 Robert M. Kalisch, note 2 supra.

9 U.S. General Accounting Office, Impact of Gambling: Economic Effects More Measurable Than Social Effects (Washington, DC, 2000), available at www.gao.gov/new.items/gg00078.pdf.

10 The $73 billion is composed of $28.7 billion (39.4%) from commercial casinos, $16.7 billion (23%) from Indian Tribal Government casinos, $19.9 billion (27.4%) from state lotteries and $7.4 billion (10.2%) from horserace wagering and charity events; see National Indian Gaming Association, An Analysis of the Economic Impact of Indian Gaming in 2004 (hereafter cited as “Indian Gaming”), available at www.indiangaming.org/NIGA_econ_impact_2004.pdf.

11 Garrett, Casino Gambling in America and Its Economic Impacts (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, August 2003).

12 IRS Pub. 1304, SOI Tax Stats—Individual Income Tax Returns, Tables 1.4 and 2.1.

13 See Indian Gaming, note 10 supra.

14 Total national casino visits of 310 million (see Harrah’s Survey 2004, “Profile of the American Casino Gambler”), divided by the national average of 5.8 times per visitor, equals 53 million individuals.

15 Foltin, “Gaming on the Rise Across America: Smart Money Says CPAs Should Take Notice,” CPA Journal (October 2005), available at www.nysscapa.org/cpajournal/2005/1005/essentials/p56.htm.

16 Edward D. Hamilton, TC Memo 2004-161.

17 Jimmie L. Clemons, TC Summ. Op. 2005-109.

18 Taxpayers may assume that if the net result of a casino session is a loss, no winnings need to be reported. However, in the process of losing, it is unlikely that there were no winning transactions. Winnings are “realized accessions to wealth” over which a taxpayer has dominion and control and, thus, are presumed to be income; see Paul F. Roemer Jr., 716 F2d 693 (9th Cir. 1983) and Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 US 426 (1955). That a taxpayer chooses to bet the winnings rather than cash them out is not determinative of their taxability.

19 Schooler, note 2 supra.

20 Regs. Sec. 1.165-10 states, “Losses sustained during the taxable year on wagering transactions shall be allowed as a deduction but only to the extent of the gains during the taxable year from such transactions. In the case of a husband and wife making a joint return for the taxable year, the combined losses of the spouses from wagering transactions shall be allowed to the extent of the combined gains of the spouses from wagering transactions.”

21 IRS General Counsel Memorandum 37312 (11/7/77).

22 IRS Letter Ruling 8123015 (2/27/81).

23 See Sec. 451(a). Regs. Sec. 1.451-2(a) states, “Income although not actually reduced to the taxpayer’s possession is constructively received by him in the taxable year during which it is credited to his account, set apart for him, or otherwise made available so that he may draw upon it at any time.” Winnings from a slot machine, for example, are “set aside” for the taxpayer, requiring only a push of the button labeled “cash out.” The regulation further states that “income is not constructively received if the taxpayer’s control of its receipt is subject to substantial limitations or restrictions.” In the case of a slot machine, there is no limit or restriction on pressing the “cash out” button (except, perhaps, the gambler’s desire for greater winnings).

24 See Regs. Sec. 1.451-2.

25 See Lutz, note 5 supra.

26 However, gamblers must request this document from a casino; it will not be sent automatically.

27 If the taxpayer-gambler is a frequent casino player and the separately paid jackpots are added back to amounts cashed out, it may be possible to use the average slot machine payout rate (e.g., 95%) to argue that the cash removed from the machine was the same percentage of the amount inserted into the machine. To date, however, there is no authority for this position in court cases or IRS rulings.

28 This issue can be confusing to the courts as well. In Est. of Graciano Espinoza, TC Memo 2005-239, the Tax Court grappled with the issue of the relative wealth of an individual who admittedly won $2.6 million playing slot machines (receiving 526 Forms W-2Gs averaging $5,000 each) and claimed to have lost a like amount. The court seemed to believe that if the taxpayer had wagered $7 million during the year, as claimed, he must have had been very wealthy. The court asked, “where did decedent [Espinoza] in 2000 obtain $7 million to play the slot machines?...Decedent apparently owed the Nevada casinos only $70,000, suggesting that decedent had access to millions of dollars.” But this confuses gross revenue with net income. If a gambler constantly plows winnings back into gambling, producing losses and more winnings, the cumulative winnings cannot be used as a measure of wealth. The winnings may be great, but the losses may be (and often are) equal in proportion. This is why it is important to look at issues of lifestyle and asset acquisition (which the court did). The assets acquired in the case included an automobile purchased “with $10,000 in cash.” For someone claiming he or she did not win $10,000, this might be a sticky point. But when the court is asking how the taxpayer acquired $7 million, a $10,000 expenditure appears immaterial.

29 Eldron Erbs, TC Summ. Op. 2001-85.

30 Erbs reported his gambling income and losses on Schedule C, claiming he was a professional gambler (which the court denied). Moving the gambling income to page one of Form 1040 and the gambling losses to miscellaneous itemized deductions (not subject to the 2% limit), and using the figures in the case, but calculating the changes using 2005 rates, he would have lost slightly over $1,200 of itemized deductions had he claimed gambling income of $325,668 ($10,538 jackpots + $315,130 from other winnings) and gambling losses of a like amount. Items based on AGI, such as the taxability of Social Security (which was otherwise nontaxable to Erbs), the medical expense deduction, IRA deductions, itemized deductions, personal exemptions and various credits, would all be correspondingly affected. In addition, the statute of limitations increases from three to six years if unreported grossed-up gambling winnings constitute 25% of the gross income originally reported on the return; see Sec. 6501(e)(1)(A). Finally, 11 of the states that impose an individual income tax do not allow a deduction for gambling losses.

31 Mary O’Hara Alsop, 290 F2d 726 (2d Cir. 1961).

32 To date, there is little evidence that taxpayers make extensive use of these year-end reports in filing returns. In Remos, TC Summ. Op. 2005-98, the taxpayer attempted to convince the court of gambling losses he needed to offset unreported gambling winnings using a Players’ Club report, but could not explain the significance of the numbers appearing on the report, or even prove that the report was issued to him.

33 More precisely, if records are available, amounts wagered on winning bets should be removed from the $341,766.95 total wagers and subtracted from total winnings to arrive at gross winnings. The net would be the same, but AGI would decrease.

34 Nick Kikalos, TC Memo 1998-92, rev’d on another issue, 190 F3d 791 (7th Cir. 1999).

35 Juan Rodriguez, TC Memo 2001-36.

Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Printable

36 Leroy V. Satran, TC Summ. Op. 2001-140.

37 Philip Stein, TC Memo 1962-19, aff’d, 322 F2d 78 (5th Cir. 1963); Plisco, 306 F2d 784 (CA DC 1962), aff’g 192 FSupp 337 (DC DC 1961).

38 Gene P. Green, 66 TC 538 (1976).

39 See also James P. McKenna, 1 BTA 326 (1925); George Winkler, 230 F2d 766 (1st Cir. 1956).

40 George M. Cohan, 39 F2d 540 (2d Cir. 1930).

Raptor Slot Machine Flow Charts

41 John David Zielonka, TC Memo 1997-81.

42 Herman Drews, 25 TC 1354 (1956).

43 Randy G. Doffin, TC Memo 1991-114.

44 Other cases in which the court applied the Cohan doctrine to estimate gambling losses include Green, note 38 supra (gambling partnership); and Kalisch, note 2 supra (horserace wagering).

Raptor Slot Machine Flow Chart Diagram

45 See, e.g., Odysseus Metas, TC Memo 1982-36; Gregory Alberico, TC Memo 1995-542; Walter E. Parschutz, Sr., TC Memo 1988-327; Tiobor I. Skirscak, TC Memo 1980-129.

46 See Mack, note 2 supra.